In the beginning, all cooking was slow. Open fires and heavy cooking pots made the quick sautés and crisp tenderness of contemporary cuisine impossible. Almost total lack of sanitation, too, made it advisable to cook food for a long time. In the mid-19th century, enclosed stoves sped up processes slightly, but meal preparation still required much vigilance. Stoves needed stoking and roasts needed basting in the dry heat of the wood stove. For most middle class American and British families, all this work was done by someone hired for the purpose—the persona known as cook. The hard work of meal production was left to those who had little time to devise easier methods.

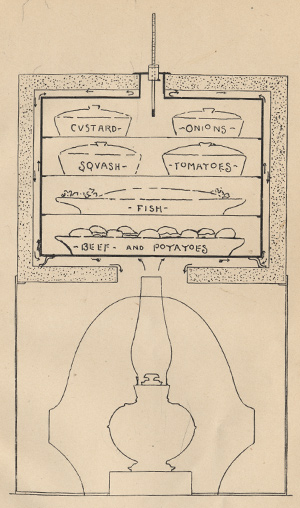

At the end of the 19th century, however, pot-watching earned a potent critic in the wiry form of Ellen Swallow Richards. An MIT-trained chemist, Richards popularized the Aladdin Oven (pictured at right), invented by Edward Atkinson. The Aladdin used one heat source (an oil lamp) to cook several dishes in separate compartments, such as beef and potatoes closest to the heat source and a pot of custard farthest away. Richards praised the Aladdin because it conserved both fuel and human energy. Its slow cooking provided another economy in that it broke down cheaper, tougher cuts of meat for tastier, less expensive meals. One company, Diller Manufacturing, claimed that its version of the fireless cooker preserved more of food’s weight and that the flavor “is cooked into the food…instead of into the surrounding atmosphere.”

The fireless cooker was not really a new idea. It simply brought indoors the technology of the luau pit or the clambake. Both these ancient methods cooked ingredients in insulated pits through the use of conserved heat.

To encourage its use in American homes, Richards featured the oven in her New England Kitchen, a short-lived restaurant designed to introduce working-class Boston to cheap, nutritious cooking. She also put the Aladdin to work in an exhibit at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, held in Chicago. There, the Aladdin fed thousands of visitors on slow-cooked fare. Because Richards was the founding figure of home economics, the slow cooker became part of education programs in this field. Home economics extension agents in the early 1900s brought stoves out to meet the people, teaching women to build their own with simple materials found on most farms.

One commercial version was the Duplex, produced in the 1910s by the Durham Manufacturing Company of Muncie, Indiana. The Duplex was a large cabinet with two insulated wells for slow cooking. It also came with heatable metal disks to be inserted above and below dishes for baking, a feature the Aladdin lacked. However, owners of the Duplex had to attach it to the only electrical source common to homes in this era—the light socket—which potentially meant that cooking was done in the dark.

Dishes had to be precooked to some degree before they were lowered into the wells. The Duplex was useful rather than magical. A promotional cookbook warned: “You can not put hastily and poorly prepared dishes in the fireless stove and take them out as delicious triumphs of culinary art.” What you could purportedly create, over the course of four or five hours, were dishes typical of middle class foodways of the era, such as veal loaf, escalloped corn, and a nice steamed pudding.

Fireless cookers became popular during the First World War when fuel prices rose and a system of voluntary rationing made the more tender cuts of meat hard to get. One popular version was the hay box (above), constructed of a cooking pot nestled inside a hay-stuffed wooden crate. As with the Duplex, food required some precooking. The cooking process had to start with braising or boiling on a stovetop before the cooking could continue slowly in the hay box.

One common problem with the hay box was that the insulation could come loose and end up as unwanted garnish to the meal. Hay insulation could also become musty, which would impart a stale flavor to the food. Most problematic was the danger of a spark at the bottom of the pan setting the box on fire. For these reasons, many women who at first had been excited about the method lost interest and, “If the family should move house, [the hay box] is left behind as a useless piece of lumber.” Like the crockpots that lurk in the backs of many contemporary cupboards, early slow cookers also waxed and waned in popularity.

Product promoter Christine Frederick wrote a cookbook for a hybrid gas stove and slow cooker called the Sentinel in 1915. Although Frederick touted the appliance’s economy, she also emphasized its liberationist potential. She had discovered the Sentinel during her “experience in trying to get away from drudgery.” Studying her own routines and analyzing letters from hundreds of women, Frederick concluded that women wasted 70 percent of their cooking time in pot-watching. One solution was to pick up the “delicatessen habit,” the early 20th-century term for relying on takeout. Frederick, however, felt obliged to provide home-cooked meals for her family.

Inspired by the women’s rights movement, Frederick also felt an obligation to herself. She wrote, “I knew it wasn’t fair or good for me to be so ‘tied down’ and unable to have recreation, or get new viewpoints of what was going on and being done outside of my own home.” Reflecting the new idea that women had a right to leisure, Frederick was delighted that while her meals cooked themselves, “I may be enjoying the second act of a popular play; I may be in church, or at the club.” Including church as a possibility was a selling point, as abandoning the kitchen might make a woman seem like a wanton hussy.

Fireless cookers were eclipsed in the 1920s by gas and electric stoves with self-regulating ovens. Being able to set the oven to a particular temperature, combined with a timer, meant that cooking required less supervision, although not quite as little as Frederick had suggested. The kind of food prepared in fireless cookers also had a limited range of textures and flavors. Fireless cookers could not fry or bake, two of America’s favorite cooking methods since the mid-19th century.

Fireless cooking remained a forgotten art until an accident of corporate amalgamation. In 1970, the domestic appliance company Rival bought a smaller competitor, Naxon. Rival commissioned a staff home economist to come up with some recipes to expand the repertoire of Naxon’s electric bean pot. In 1971, when her booklet went out with the newly christened “Crock-Pot,” a trend was born and other companies began to copy the idea, calling their products “slow cookers.”

Like Christine Frederick 60 years before him, cookbook writer Carlson Wade also promised that “the slow cooker gives you carefree cooking. There’s no need to remain imprisoned in your hot kitchen…watching the meals.” It was 1975 and the second wave of the women’s movement was well under way. While glass ceilings shattered and bras smoldered, Wade’s message would have had a strong appeal. Slow cooking even had a role to play in the sexual revolution. A recipe column in Playgirl magazine the same year celebrated the crockpot’s ability to free up women for extended sexual encounters: “Perhaps you’d thought of bed after [dinner], but it’s getting more and more obvious that it’s dinner that will have to wait.”

Ubiquitous during the 1970s, the slow cooker was once again eclipsed in the 1980s with the rise of nouvelle cuisine. Cookbook author Lora Brody recalled, “As cooking became more of a leisure activity and sexier equipment, such as gleaming copper pots, turbo food processors, and espresso/cappuccino machines, became kitchen essentials in many homes, the slow cooker was shoved farther back in the closet, stored in the basement, or sold off at yard sales.”

Brody wrote her remarks in 2001, which was a period of resurgence for the slow cooker. New technology made the pot programmable so that it could be set to start cooking when no one was home. The crockpot and its ilk fit well with the early 20th-century fad for comfort food. It also complemented the new work culture, which required long hours from professionals. A woman could work 60-hour weeks as an executive but also provide for her family and tap into trends if only she loaded up the crockpot early each morning.

In 2007, Beth Hensperger, author of several books about slow cookers, also tied the appliance to contemporary themes in food writing. “I am a proponent of wholesome, fresh food,” she wrote, and “easily obtainable seasonal ingredients.” Using the language of the locavore, she claimed the slow cooker “fits into not only my food philosophy, but my time schedule as well.” Always praised for saving time, the slow cooker may now attempt the role of socially conscious cookware. But it still can’t fry an egg.

Megan Elias is the author of Stir It Up: Home Economics in American Culture and Food in the United States, 1890–1945. She previously wrote about the history of the word gourmet in Gourmet Live.