A meal that results from your own hard work is strong juju. A few years back, I turned my backyard in Flatbush, Brooklyn, into a farm and—with the notable exception of salt, pepper and coffee beans—lived off only the food I grew and husbanded back there. For nearly 60 days running I ate roast chicken, collard greens and tomatoes for dinner. I’d be a liar if I said it didn’t get boring, but I’d be as guilty of understatement if I didn’t declare that (other than fatherhood) building and maintaining my little farm and harvesting livestock and produce from it was the most satisfying accomplishment of my life. This lent form to a passion that has always lived inside me, and it birthed a movement: Stunt Foodways. It’s about cooking crazy with conviction.

“Foodways” is the term for why we eat what we eat, how, and with whom we eat it. Anthropologists study foodways the same way they pore over folktales, and scrutinize hand tools—for crucial insight into a culture. Once upon a time, it was the foodways of far off, exotic places that grabbed the attention and imagination of social scientists. In 1989 Carlo Petrini founded Slow Foodways to confront the gustatory chaos he believed fast food had inflicted on his beloved Italy. It is now an international organization. In the United States, we have regional outfits like the Southern Foodways Alliance. Founded in 1999 by John Egerton of Birmingham, Alabama, this one promotes and preserves the robust and finely textured culinary tradition of the South Eastern United States. If those folks who are committed to urban agriculture don’t already have their own foodways institute, they will have built one before the next harvest. So, what is Stunt Foodways? Stunt Foodways promotes the adventure in every meal by celebrating the fever dream of overly ambitious cookery. It is not about eating bugs and grubs. That’s nasty.

Stunt Foodways is a dedication through work (occasionally grueling and ceaseless) to the fair and honest treatment of ugly and ungainly food. Stunt Foodists are fanatics of the whole critter and the marginal meat. We are also committed to feeding unruly crowds. Because only by cooking hard and well beyond one’s pay grade can one hope for great joy and binding fellowship at the table.

The ways of Slow Food and Stunt Food do share many goals, but very few practices. Waging their holy war against modernity and its primary vice, speed, the occasionally precious followers of Slow Food concern themselves with meals that are “good, clean, and fair.”

Bully for them.

Thanks, George. Amazing feed. Hey, and don’t forget to send along the recipe for that watermelon pickle.

In the pursuit of food that is fun, great, and a helluva a lot of work, Stunt Foodists confront nothing less than the denial of death. Scoff if you like. There’s no escaping it, though; you know it in your bones. Your next meal could be your last. Whenever that day does arrive and your kinfolk gather around, will your eulogy be delivered, as your pizza was, by the bland herald of efficiency? Will it tell the flaccid tale of another fallen servant of convenience?

Or will your people celebrate the life of a true hero of the dinner table?

Now let me be clear, Stunt Foodways is no post-millennial urge, no leading trend. Stunt Foodists were present at the creation. Indeed, every great moment in history has its great meal (The Great Meal Theory of History) and every great meal was put on by a Stunt Foodist. During the dark days of the Trojan War, Achilles and Odysseus enjoyed a baroque battlefield meal of a sheep’s back, whole goat, and a chine of a wild hog, “first knitted” (whatever that is), carved, salted and roasted on a spit. Now that’s a meal strongly rooted in the tradition.

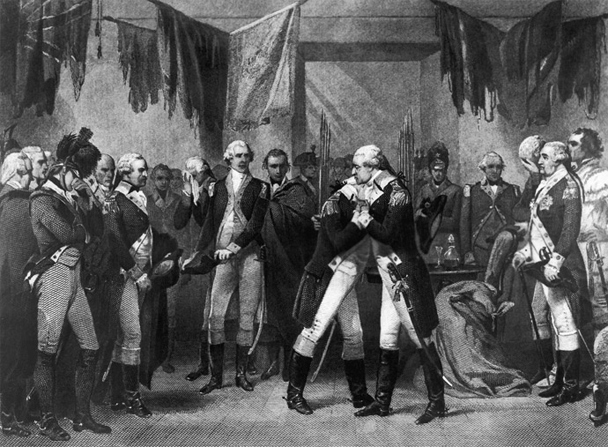

Again, in December 1783, after the victorious colonial general’s historic farewell address to his troops, George Washington hosted a feast for 80 men—his own and officers of the allied French army—at Fraunces Tavern. The offerings included cold poached striped bass with cucumber sauce, mushroom pastry, steak and kidney pie, roasted lamb stuffed with oyster forcemeat, smoked country ham with Madeira molded wine jelly, and watermelon pickles with pear honey. What identifies our foundingest father as a fellow traveler is not simply the ambition apparent in the menu he selected, but his enthusiasm for a crowd.

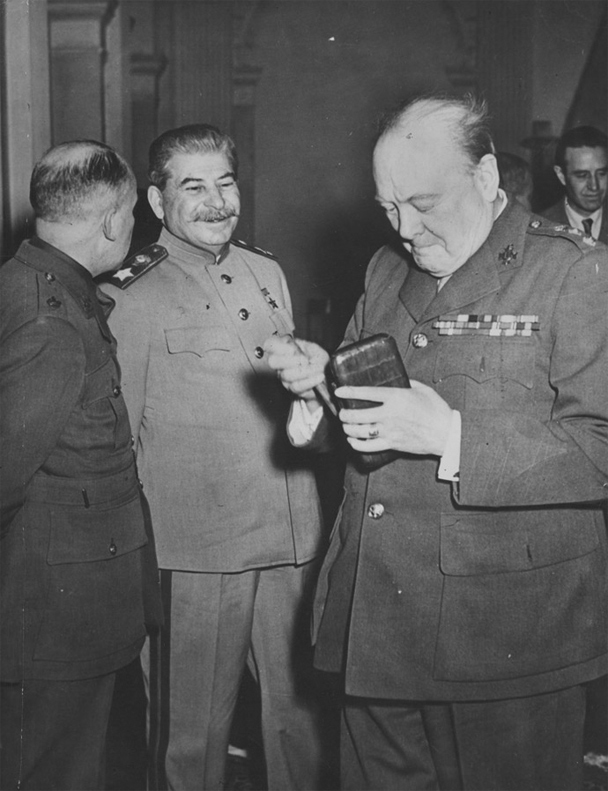

More recently, at The Fourth Moscow Conference in October, 1944, while negotiating the terms of what would be The Yalta Agreement, Winston Churchill and Josef Stalin ordered up feasts of suckling pig, roasted chicken, beef and mutton for the British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden and the Soviet foreign minister, Vyacheslav Molotov.

“It’s just dinner.” You hear this wail of the defeated uttered every day. It is the weak mantra of the feeble hordes ignoring the truth that we each have but a fixed number of meals ahead of us. No matter how tempted to convenience fodder by the confounding, maybe infuriating events of the day we are, relegating even one meal to the slagheap of nutritive necessity is a dreadful act of submission.

Stunt Foodists are the sworn enemy of The Clock. This is not simply a metaphorical antipathy. Cooking crazy with conviction requires dedication but it also takes time. Standing one’s culinary ground after homework on a Wednesday will most certainly result in disaster, and domestic havoc is the reward of every Stunt Foodist. I’ve been heard to bark over my shoulder at my starving children, forbidding them one more rice cake, whilst whisking away at a sauce on the stovetop, assuring them (the ingrates!) that dinner will be served after I have deglazed the pan...and not one minute before. Kids don’t get to bed on time; even the most appreciative spouse gets fed up. Dishes get done alone in glum silence.

We know the terrible price, which is why trite entreaties to seize life through cookery are beneath the Stunt Foodist. What separates us from the flabby, jabbering mass—the saccharine television hosts, self-satisfied recipe pimps, critics, and columnists, the lot of them—is the understanding that good cooking is much more than a life-affirming exercise. It is the belief that when performed at the highest level, cooking is a contact sport. It comes with glorious rewards and stupefying defeats. Success is not a requirement of stunt cooking, but neither is success the only marker of victory. We are concerned with the journey, less so with the result.

Don’t get me wrong; success is preferable, and last-minute saves make up the great myths of our tradition. But the failures are equally spectacular—if not more so. I have witnessed a DIY spit crafted by a fellow Stunt Foodist fracture under the weight of a side of beef and collapse into the inferno below. I’ve watched in awe while the deep-fried turkey (remember them?) I was preparing for 18 hungry and drunken guests disappeared into an angry vat of roiling peanut oil never to be seen again.

Shit yeah, we served suckling pig. And Winny got falling down drunk, as usual. Late start in the morning, but the feed was worth it. Good times. Can’t wait for Yalta.

Most recently I came to posses that rare treasure, a Kobe beef tongue. The plan was to prepare slices of seared tongue for my father who has frequently regaled me with tales of grand, white marble edifices dedicated to the sale of countless varieties of tripe, and ripping yarns about the many marginal meats available in England during The War. So I boiled the tender Kobe tongue in a carefully prepared spice broth, tending it lovingly as it cooked. In my haste to impress my father, I ignored the central commandment of the tradition: “Great food takes a long time: Sometimes days, sometimes longer.” Forsaking the strict instructions of fellow traveler Brad Farmerie, the chef/owner of restaurants Public and Double Crown in NYC, that I be sure to take care and let the tongue rest and cool over 12 long hours, I cut a corner, and plunged the flesh in an ice water bath. The tongue I fished from its watery grave 45 minutes later was ruined. The once impossibly delicate meat was now a knot of furious flesh, unyielding to ministrations and massage, tough beyond repair.

Still, I sliced it fine and prepared the heavy skillet to receive the angry tongue, steeling myself by remembering the Stunt Foodways motto: In Dubiis Constans (“steady in doubtful affairs”). As I stood trembling at the stovetop watching over the ever contracting tongue, the Second Commandment of stunt cookery steadied me: Try Again Later.

Dad and I spent the entire meal marveling at how much worse the dinner could have been and commemorating past failures, notably a whole rabbit prepared with sour cream. “Why you left the head on, I’ll never know!” my father exclaimed. “I was thinking of the presentation,” I protested. Both laughed.

It is often assumed that Stunt Foodways are male ways. Not so. There was no more dedicated Stunt Foodist than Julia Child, and, while Georgia Pellegrini, the Girl Hunter, is no Julia Child, she certainly cleans up in the firepower department. A similar misconception is that people with no interest in blood sports need not apply. While it is true that an instinct for The Stunt in cooking often begins with protein acquisition, it is not a requirement that animal be turned to flesh by one’s own hand. Sure, Stunt Foodists can be found in deer blinds, or marching through grain fields with working dogs and shotguns, or trudging along the beach, surf rod in hand—but we also frequent live poultry markets, Halal butchers, and pork specialty stores. I’ve even seen one or two in the aisles of Whole Foods.

Commandment Number Three: You need not be a butcher, but you should get to know one. It’s true that a commitment to the whole beast or primal cuts—those bold divisions better accomplished with a band saw or an axe than a knife—is a hallmark of Stunt Foodways. The charts detailing the various divisions of goats, pigs, sheep and cows adorn our walls and our imaginations. Enrollment for classes in butchering and related arts—once considered as counter cultural as yurt-living—increases every month. The sale of Hummer-sized barbeque grills are booming (sort of). If you have had a chance to peruse the kitchen tools section of the 2011 edition of Cabela’s Master Catalog you’ll observe that the management at the world’s vast outdoor adventure retailer is evidently expecting to add its share of Stunt Foodists to the client base. We have always been among you. We were the heroes of past eras. We are the heroes of the 21st century dinner table. We prepare for death by filling our lives with adventure one mouthful at a time. We are Stunt Foodists. Join us.

Manny Howard is the founder of Stunt Foodways International and is a James Beard Foundation Award-winning journalist. He has written for The New York Times Magazine, GQ, Travel & Leisure, New York Magazine, The New York Observer and more, and he has appeared on The Colbert Report. Howard is also the author of the runaway hit memoir My Empire of Dirt and contributed (along with Stephen King, Jim Harrrison and Mario Batali) to the essay collection Man with a Pan.