My grandfather once wrote, supposedly paraphrasing a good friend of his, “There are two lasting bequests we can give our children: one of these is roots, the other is wings.”* It’s solid advice, simultaneously enshrining the nuclear family, while challenging us to remain open to change—if not for our sake, then for our children’s. Strong words to live by, and all that.

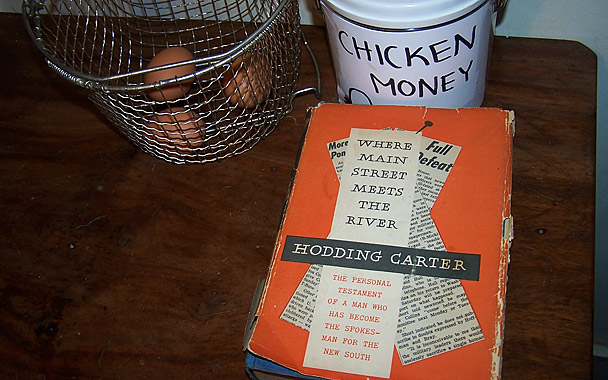

You’ve probably seen the quotation on a greeting card or two, or on quite a few website homepages. Maybe some of you figured out my kinship to the author (same name) and were wondering how I could be so income-challenged, for some reason discounting my public mea culpa. Now, if my grandfather or his children had only copyrighted the phrase, I might not have had to recently pay for dog food by trading in three trash cans of returnables. But we never cashed in. My dad says it simply didn’t occur to him until he suddenly saw the quotation everywhere he looked.

Despite its popularity, most people haven’t followed its fairly simple advice. Lately, it seems we’ve been getting and using our wings just fine. We flit from place to place and person to person like some rabid combination of Tinkerbell, Cupid, and Daffy Duck. But how about those roots? We’re unable to withstand the slightest breeze, as witnessed by our country’s skyrocketing divorce rate, legal suits, and, now, foreclosures. We more closely resemble the unanchored white spruce trees that topple down day after day, year after year all over Maine’s rocky islands than the deeply rooted oaks and pecan trees that my grandfather imagined. Is it TV? The on-the-go consumption of fast food? Parasitic companies jumping from one state’s expired no-tax offer to another’s, scattering legions of rootless workers behind them?

I don’t know.

I do know there’s something about this frugal living that’s re-forming my children, driving their roots deep into our literal and figurative surroundings, at a pace that all my indulgent spending never accomplished. If roots mean a mindfulness of disparities in wealth, a concern for the entire family’s well-being, nascent compassion, a willingness to pitch in, a growing desire to help change our ways, and a clear understanding of who we are as opposed to who we project ourselves to be; if having roots means possessing and cherishing these qualities, then I’d say we are finally heeding my grandfather’s advice.

Last October, as I frantically stomped through the boggy woods behind our house searching for standing dead wood that I could cut and chop for our woodstove, I suddenly remembered there was a better way to get around shelling out $20 for a quart of maple syrup every month (it’s getting even more expensive). We had dozens of maples, mostly scrub, but maples nevertheless. This realization was one of the first in an ever-increasing succession of positive realizations that things were going to be more than okay—they were going to be a damn sight better. As I ambled around the woods marking maples, I stopped panicking, but it was when I started listening to my children that I had something even better: hope.

Yesterday, when I picked the kids up from school, I knew they were developing the kind of roots Big (my grandfather’s nickname—really) was talking about. Thirteen-year-old Anabel climbed into the back of the minivan, not with the ever-present teenage scowl but with a teasing smile as she asked, “Dad, I think you’ve forgotten about something.” Nothing unusual there, I thought—it’s a breakthrough day when I remember to put my pants on before heading out the door. “All those maples you painted blue? It’s time to tap them. Can we do it tomorrow?” Anabel is the same daughter who recently offered to buy the party favors for her own birthday celebration. The same girl who, back in October, angrily stated she wasn’t going to live frugally with the rest of us.

Eliza, Anabel’s twin, who once only wanted the most popular brands of ice cream and clothing, now runs through the store looking for generic or reduced-for-quick-sale items. She doesn’t let me buy name-brand anything and recently scolded me as I absentmindedly picked up a liter of bottled juice: “Put that back. It’s much cheaper to make our own. Mom said so.”

And then there’s Helen, the one who nearly cried when Lisa and I said we had to cut back our spending. She has lived for fine dining most of her 11 years, but not anymore. “We get to make lots more good stuff and it tastes better,” she claimed, and then she added, almost making me wreck the car, “I don’t ever want to eat out again.”

And then there’s Angus, 6, keeping things real. He recently announced we could sell his toys. When Lisa congratulated him, however, he quickly made a clarification: “I meant the broken ones!”

Hope that brings a tear of joy to all those “Go out and shop!” economists.

Amount spent yearly on maple syrup: $200

Money saved if we make all our own syrup: $188

Cost of metal tap to collect maple sap: $2.97

Number of taps bought: 4

Number of taps we desire: 12

Time it takes to collect 1 gallon of sap from Carter family midsized maples: 3 days

Cost of heat to boil sap: Free (outdoor wood fire)

Number of prime sap-collecting days during an average Maine spring: 2 weeks

Number of Carters who like maple syrup: 4

[1] *Most people attribute the advice to him, although some suggest Henry Ward Beecher said it first, and still others quote a similar bit of wisdom uttered by Jonas Salk—after my grandfather’s book Where Main Street Meets the River, which contains the quotation, was published. Here’s the remainder of the quotation (I like it as much as the over-used part): “And they can only be grown, these roots and these wings, in the home. We want our sons’ roots to go deep into the soil beneath them and into the past, not in arrogance but in confidence.”