My mother edited the Poultry and Game chapter of A Grand Heritage, the community cookbook published by my high school in 1983. She held editorial meetings in our dining room, discussing how this book, though still a comb-bound volume, was going to have professional styling and color photography. The cover photograph—a lavish array of desserts on a silver tray—was shot on our front porch.

That spiffy new approach was part of a trend that has unfortunately made today’s hardcover, four-color affairs—worthy of sitting alongside professionally published chefs’ tomes—a lot less fun to read.

I treasure my old community cookbooks specifically for their slipshod editing (three Seven-Minute Frosting recipes in the same book), dubious storage advice (a cole slaw “keeps indefinitely”), and dishes that sound inedible (Velveeta plus Miracle Whip plus canned tuna equals a “speedy dip for unexpected company”). Many new community cookbooks are better organized, more standardized, and error-free—and thus, more predictable.

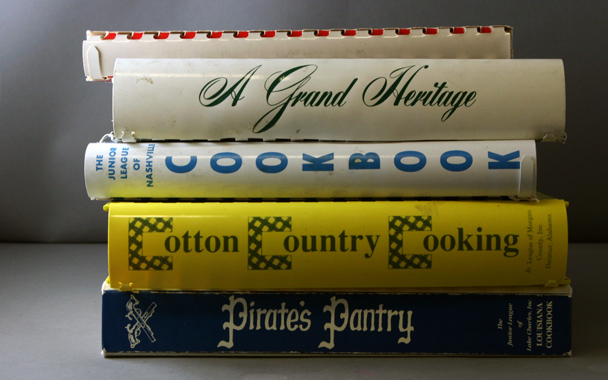

Give me a poorly proofread, typewritten, and photograph-less volume of favorites from Demopolis Academy (The General’s Second Helping, 1977), with its “Crabmeat Rockerfellow,” or a collection of recipes from the Junior League of Nashville (Nashville Seasons, 1952), with its blue-blooded assumption that you own a silver tray on which to present an Orange Bombe.

The range of recipes in the old books is another bonus. You got a recipe for Sweetbreads Perigord opposite one for Baked Brisket with Pepsi, twenty gelatin salads and more cakes than you could make in a year, and meal ideas for the squirrels your teenage son shot down from the tree in your backyard. And each cookbook committee organized those recipes differently. In A Grand Heritage, Cheese, Eggs, and Grains (including, yes, pasta) are lumped together; in Southern Accent (Junior League of Pine Bluff, Arkansas, 1976), pasta and rice are grouped with vegetables. Some books, eyeing the market’s want of distinction, include special sections for party, picnic, and foreign foods. My personal favorite is the chapter by the community’s husbands, provocatively titled “Men.”

Then there are the recipe names. Some conjure images of housewives swapping recipes over the backyard fence: “Con’s Chocolate Cake,” “Mae’s Dirty Rice,” and “Shirl’s Salad Dressing” seem like lucky finds, well-kept secrets finally shared. Others flaunt worldliness with Frenchified titles—“Poulet a la Stanley”—and recipes named for places where the cook sampled them—“Lehigh Valley Shrimp Mold” and “Alabama Salad.”

The contributor’s name at the end of a recipe yielded volumes of information about the status of women’s social standing in the community. Pre-women’s movement, books often featured formal names, for example, Mrs. John Sharp. Whether she was Betty or Eleanor or Mary was irrelevant (even if she was the one with all the money). If she and Mr. Sharp divorced, the name beneath her Salmon Mousse became Mrs. Patricia Snelling Sharp. This is what Emily Post proscribed, but I feel it’s embarrassing for the divorcées. Their names stand out amidst all of the others, as if the divorce itself wasn’t enough of a bummer. Along these same lines, a contributor’s hometown was noted if she was an outsider. This distinction adds a subtle exoticism and reverence to the recipes whose donors came from New York City or Washington, D.C., places where you might see Jackie O. on the street.

But all of this is missing in the latest editions of community cookbooks. Most still feature the contributors’ names, but in miniscule type at the end of the book. And I feel cheated. Unless the names are paired with the recipes, how can you imagine the dining room where Mrs. Robert J. Warner of the Junior League of Nashville presented her Cream of Crabmeat Soup, followed by her Lobster Newberg II? Or the lake place in Ontario that inspired the name of the Ground Beef Muskoka casserole shared by Mrs. Stuart C. Irby of the Jackson, Mississippi Symphony League? You can’t. Nor can you tell who was ripping off Julia Child and who was a back-of-the-can cook.

The biggest loss, though, is that many of the newer books have edited out the winsome tag lines from the editors and contributors. Some advise successful pairings (“Very good with lamb”), others, an appropriate occasion for the recipe (Cheese Mold with Strawberry Preserves is “good for an afternoon sherry party”). It’s not uncommon for the tag line to boldly express the cook’s misgivings: “This recipe always brings lots of conversation. People are not really sure what they are eating,” notes Mrs. Bert Parrish of her Baked Apricots in Nashville Seasons. Or consider the appeal of the Pirate’s Pantry (Junior League of Lake Charles, Louisiana, 1977) recipe for Brisket, whose clincher is “Looks strange, but a guaranteed delicious dish.” Some cooks offer a refreshing frankness about the popularity of their dishes, as Mrs. James F. Hooper, Heritage Academy supporter, does with her Bagna Calda: “Some like it and some don’t!”

The paragon of such writing is Cotton Country Cooking (Junior League of Morgan County, Alabama, 1972). Here, the editorial team promoted nearly every recipe with italicized come-ons: Don’t be one of those who says ‘I just can’t fry chicken.’ Follow these instructions and it will be perfect—every time. Alongside such housewife-y encouragement lurks a frisky subtext: Watch the men line up at your kitchen door when they smell these little pizzas cooking, says the recipe for Pizza Hors d’Oeuvres. The Shrimp Spread claims to be another way to get him. Gunning for a new party dress? Corn Casserole is a hearty dish and a real husband pleaser. But for some real fireworks, consider Cornish Hens as a marital aid: Put the children to bed early and surprise him.

If you ask me, all of this makes for good cookbook reading. The refined, glossy new books are perhaps better at presenting recipes and the community’s official history, and the color photographs, like the one taken on my porch back when the change was coming, are indeed lovely. But I still think that the newest releases are missing local color. It’s in the old books, though, right there in black and white.

What do you think of the new community cookbooks versus the old? Any local favorites?