Left image by Bettman/Corbis; Right Photograph by John Kernick

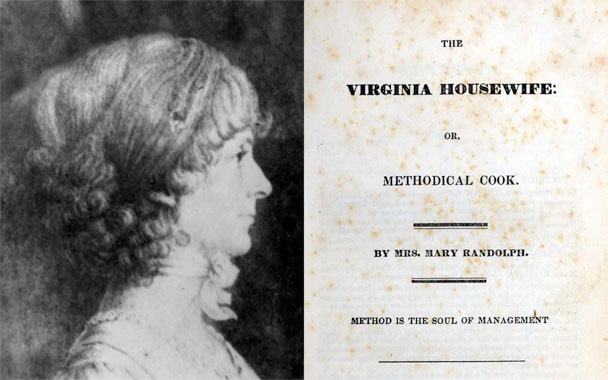

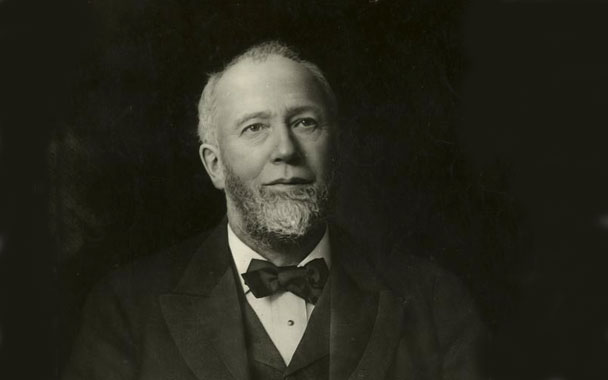

Left image Courtesy of The Library of Virginia

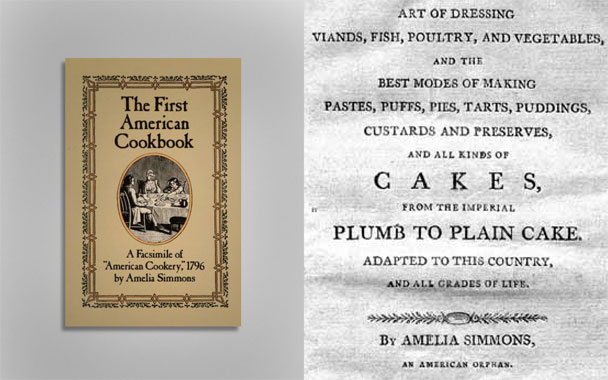

Image Courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia

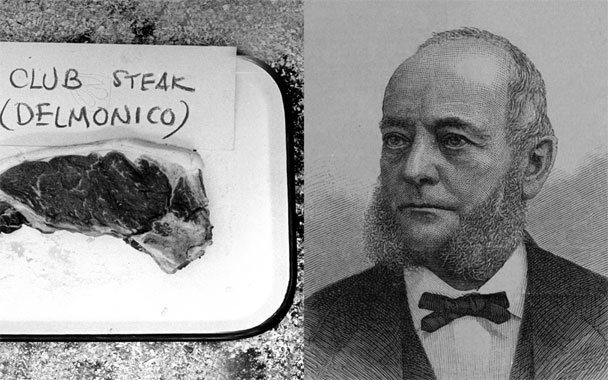

Left Image Courtesy of The Granger Collection; Right photograph by Cannon Brown

Images Courtesy of Michigan State University

Image Courtesy of NYPL Digital Gallery, The New York Public Library

Left Photograh by Time & Life Pictures/Getty; Right Photograph Courtesy of NYPL Digital Gallery, The New York Public Library

Photograph Courtesy of the Fred Harvey House

Image Courtesy of NYPL Digital Gallery, The New York Public Library

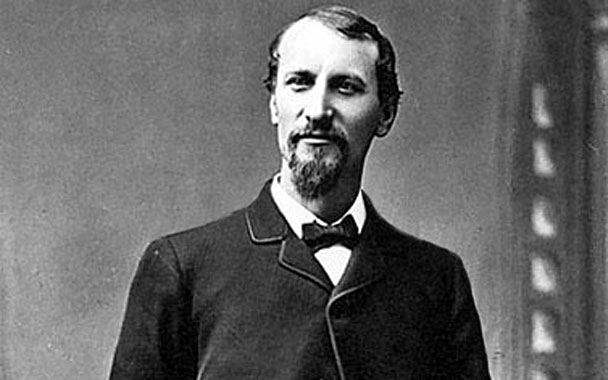

Photograph by B.M. Clinedinst/ Corbis

Image Courtesy of NYPL Digital Gallery, The New York Public Library

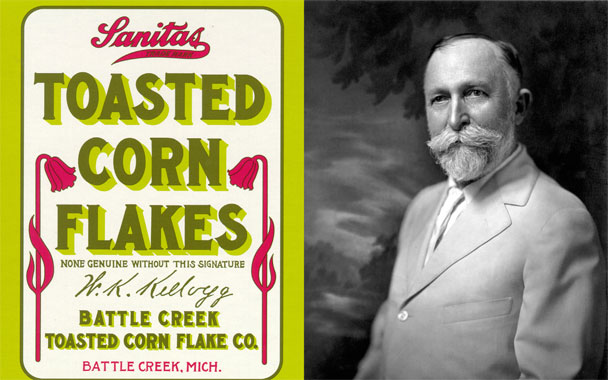

Left Image Courtesy of The Kellogg Company; Right Photograph by Corbis

Photograph by Bettmann/Corbis

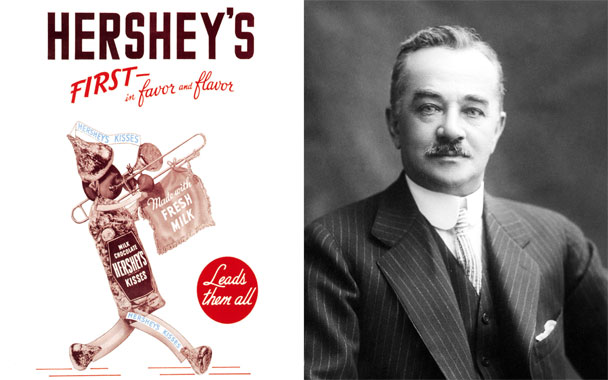

Left Image Courtesy of The Hershey Company; Right Photograph by Bettmann/Corbis

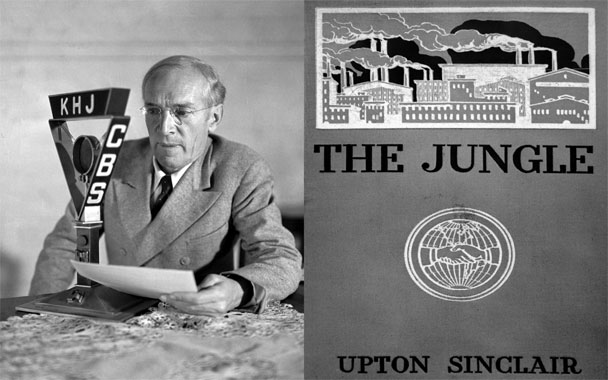

Left Photograph by AP Photo; Right Photograph by Bettmann/Corbis

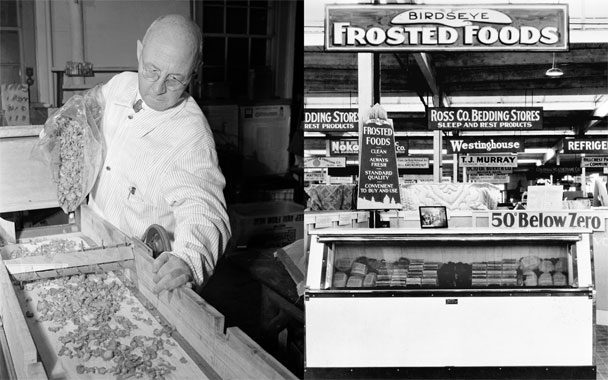

Left Photograph by Bettman/Corbis; Right Photograph Courtesy of Birdseye

Photographs by Time & Life Pictures/Getty

Photograph by Time & Life Pictures/Getty

Left Photograph by Time & Life Pictures/Getty; Right Photograph by AP Photo/Rich Kareckas

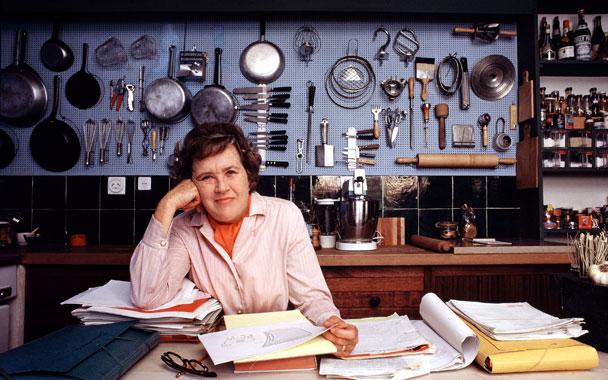

Photograph by Time & Life Pictures/Getty

Photograph Courtesy of University of Minnesota

Photograph by Arnold Newman/ Getty

Photograph by Chester Higgins Jr/ Redux

Photograph by Anna Lappé