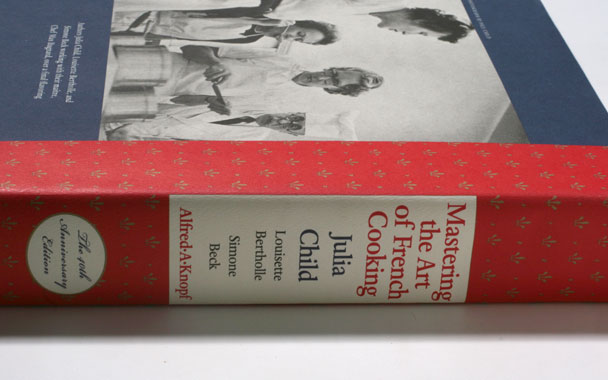

The fact that Mastering the Art of French Cooking—a great, eternal gift to American home cooks—got published at all is a miracle, because nothing like it had ever existed before. Julia Child’s collaboration with her Paris cooking-school partners, Simone (Simca) Beck and Louisette Bertholle, was as complicated as marriage, and epic battles ensued as they shaped the book into one conveying not just that cooking is an art, but that learning to cook is a lifelong process that happens to be enormous fun. As the book progressed, Julia and her husband, Paul Child, a diplomat, were transferred to Marseille, and then to Germany and Norway. Everywhere they went, they lugged kitchen equipment, a typewriter, and two steamer trunks filled with pounds of manuscript pages, reference books, notes, and air-mailed critiques from family and friends back in the States, who tried the recipes with American ingredients. Julia and Simca tested and retested recipes obsessively, creating revolutionary—and foolproof—techniques for hollandaise, mayonnaise, and beurre blanc in the process. American publishers didn’t know what to make of the finished manuscript (which included suggestions on cookware, menu planning, and wine as well as plenty of solidly researched practical tips) until it landed with a thump on the desk of Judith Jones, a young editor at Alfred A. Knopf, who immediately understood the importance of the achievement. The advance was $1,500, and the book was first published in 1961.

My mother, who generally would rather have been curled up with a novel than standing behind the stove, dropped everything and rushed out to buy it. The Kennedys were in the White House, and she thought the First Lady’s interest in European culture was refreshing. “Boeuf bourguignon,” she read aloud, sitting at the kitchen table. “Blanquette de veau à l’ancienne.” I was six, and had no idea my mother could speak another language. “Poulets grillés à la diable,” she continued, “broiled chicken—that’s easy—mmm, with mustard, herbs, and bread crumbs. Served with chilled rosé wine. Goodness!” Dinner that night was simple and familiar, but “What in the hell is on the flounder?” Daddy asked. “Buerre maitre d’hôtel,” Mom replied silkily. Daddy chewed a moment and swallowed. “Sure is good,” he said.

I wish I knew what happened to that book. I don’t think Mom ever attempted the veal, but that boeuf bourguignon appeared regularly for a long time, as did that mustardy chicken. When I moved to New York, it was my good fortune to work at Knopf, and Mastering the Art of French Cooking soon came home with me. It taught me what real French dressing was, how to deglaze a pan, the value of eggs (the cheapest, most nourishing supper in the world), how to laugh at a culinary disaster and try again. The first time I went to Paris, I knew enough to get myself to Dehillerin and buy a small copper pot and a glazed earthenware casserole, in which everything I cook tastes delicious. On my last visit, I found myself studying a menu and ordering, in some bemusement, poulets grillés à la diable. It tasted exactly like my mother’s. And she would have loved the rosé.